Your Identity Is Not a Mental Health Risk Factor

Risk and resiliency in the sexual and gender minority communities

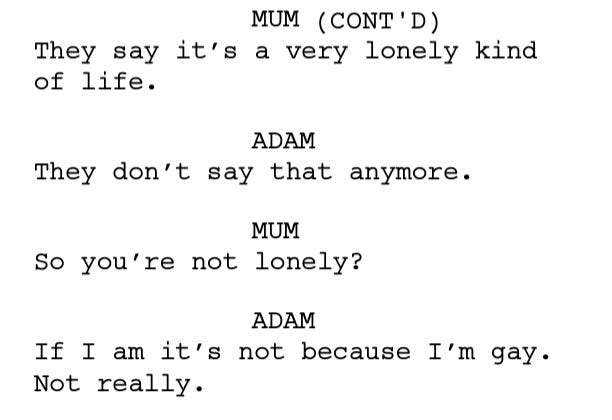

I recently watched the film All of Us Strangers, a surreal story about a character who is given the chance to talk to his long-dead parents. Without spoiling too much, there’s a pivotal scene where Adam, a man in his 40s, comes out to his mother, who died when he was a preteen. She is less than supportive.

In my memory, Adam takes a long pause before answering his mom’s question about whether or not he is lonely. To this point, we don’t know a lot about Adam, but one thing is certain: He is incredibly lonely. But clearly he is defensive when trying to answer this question as it relates to his sexuality to his dead mom. It’s complicated.

June is Pride month, dedicated to acknowledging the struggles and celebrating the accomplishments of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans communities. Unfortunately, it’s becoming a tradition in the United States to contend with the myriad ways these communities are under attack, from state courts blocking the protection of sexual and gender minority students from Title IX protections to the fearmongering over gender transition in young adults.

In addressing these discriminatory and prejudiced policies, many will cite the vulnerability of these groups, particularly as it relates to mental health as LGBTQ+ individuals are at significantly increased risk of suicide compared to the general population. For example, the Trevor Project estimates that a young person in the United States who identifies as a sexual and gender minority attempts suicide every 45 seconds.

Ungracious interpretations of such data might suggest that identifying as a sexual and gender minority is itself a “risk factor” (i.e., something that increases the likelihood of experiencing an outcome) for developing mental health concerns. Indeed, the basis of unethical and scientifically unsupported practices1 like conversion therapy treat being queer as something unwanted that should be “cured.”

As someone interested in how various identities intersect with mental health, I try my best to remain vigilant about how these issues are discussed for fear of perpetuating the false notion that there is something inherent about an individual’s race or gender identity that causes them to have poorer mental health. Rather, across minoritized groups, the evidence shows us again and again that it’s not about the individuals themselves, but the way that society treats these individuals, that puts them at heightened risk for mental health concerns.

Take, for example, the results from the 2015 Transgender Survey, the largest nationwide survey attempting to understand suicidal thinking and behaviors in trans adults. Almost 82% of respondents discussed thinking about suicide seriously in their lifetimes, with 40% reporting at least one suicide attempt. Within these communities, some risk factors for suicidality were similar to what we see across all people (e.g., poor general health, alcohol/drug use), while others were specific to the experiences of being trans. Experiencing discrimination or mistreatment, rejection from family or religious communities because of one’s gender identity, experiencing violence, and “de-transitioning” were all related to an increased likelihood of a respondent describing suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Researchers sometimes refer to the collection of experiences like these that inordinately harm minoritized communities as “minority stress.”

On the other hand, researchers also examine “protective factors,” or things that help reduce the likelihood of an unwanted outcome (e.g., thoughts of suicide) or increase the likelihood of a desired outcome (e.g., better mental health). In relationship to minority stress, we can also think of these experiences as “resiliency” factors, or things that predict one’s ability to adapt and cope with stress. When respondents reported that they had supportive families, could access hormone therapy and/or surgical care when they wanted to, and lived in a state with a gender identity nondiscrimination statute, they were less likely to report suicidality.

Similar risk and resiliency factors were found in a review on sexual and gender diverse childbearing experiences. LGBTQ+ parents discussed difficulties unique to their journey to parenthood, including structural exclusion (e.g., language on medical forms and birth certificates), discrimination (e.g., inability to access parental rights, required disclosure of one’s sexual or gender identity to access medical care), and gender dysphoria. At the same time, themes of resiliency were prevalent, including finding culturally competent medical providers, seeking support from other sexual and gender diverse parents, and celebrating their ability to “queer” or create alternative narratives to the heterocisnormative traditional family (e.g., resisting gendering a child, forming family units outside of romantic partnerships).

All of this is to say that it can be easy to fall into the trap of only talking about the negatives of sexual and gender minority experiences as they relate to mental health. I don’t want to trivialize these very real concerns, but it’s important to be specific about where the harm comes from and to always emphasize that there’s nothing inherently wrong or bad about any sexuality or gender identity. Certain groups are vulnerable to harm because the world decides to harm them. By focusing on what heals these communities and what can prevent this harm from occurring, we can get that much closer to building a world where fewer people need to learn how to be “resilient.”

Going back to the conversation between Adam and his mother, there are a variety of reasons Adam is lonely. Being gay is only part of his story, as it would be for any individual. Similarly, the film is not just about Adam coming out. It touches on many themes, such as the burden of grief and how closing yourself off from the world hurts others just as much is it hurts you. When I was looking back at the script, I was struck by the last words included before the end credits:

A guide not a warning. “Make love your goal.”

Other recommendations:

Glamour and the organization Paid Leave for All are advocating for universal paid parental leave. They cite statistics that are particularly relevant for LGBTQ+ parents, including that 64% of companies do not offer paid leave benefits for parents going through adoption and 51% of the LGBTQ+ population live in states lacking paid leave polices. You can sign the petition here

I liked this interview with psychologist Abbie Goldberg on how to support sexual and gender minority parent families (from the newsletter Is My Kid the Asshole?)

I think a lot about this article on The Rise of the Three-Parent Family (The Atlantic) and how asexual individuals are underdiscussed when we talk about sexual and gender diverse communities

Emily St. James has been one of my favorite writers for decades. She’s adopted, she’s from the Midwest, she’s a parent… we’re basically twins. I love her writing on TV and movies (like her take on Barbie), but she also writes compellingly about the trans experience. I recommend all of her writing, but here are a few standout pieces:

What’s so scary about a transgender child? (Vox): An in-depth piece arguing the basic premise of: “Stop worrying about what happens if we let kids transition. Worry about what happens if we don’t.” It expands on themes around the trans experience and mental health that I only touched on

Hypothetical Children (Episodes): Similar to the article above, Emily argues the way some in our society prioritize hypothetical children (the unborn, those who may later regret gender transitioning) over real ones. The last paragraph is particularly powerful:

We use hypothetical children in so many circumstances when it becomes inconvenient to consider the existence of real ones. Whether we are trying to ignore the mass-murder of children in an ongoing war or look away from the endless parade of deaths in school shootings, we are constantly prioritizing the hypotheticals we can most easily picture over that which is actually happening. We stick with what is hypothetical because it asks the least of us. When reality becomes too inconvenient or painful to look at, we can always burrow further into the moral simplicity of our imaginations, where we are always careful to protect ourselves and almost no one else.

If you’re an educator or simply interested in assessing the diversity of media your child consumes, I was recommended this culturally responsive scorecard resource by the Education Justice Research and Organizing Collaborative (hat tip to my friend Noah for sharing this!)

There are a host of podcasts that do a great job discussing psychology’s complicated history with LGBTQ+ communities. Here are a few:

Conversion Therapy (Part 1) (Sawbones): A discussion of the history of conversion therapy and how screwed up it is that this is still being practiced in modern society

81 Words (This American Life): How the American Psychiatric Association decided in 1973 that homosexuality would no longer be considered a diagnosable mental illness

Kitty Genovese and “Bystander Apathy” (You’re Wrong About): If you took Psych 101 (or watched that episode of Girls), you probably learned about the murder of Kitty Genovese and how dozens of witnesses failed to come to her aid or call the police. As you might guess, the story is a lot more complicated than that. This podcast dives into those details, including how many accounts completely ignore/discount Genovese’s sexuality

There are studies that purport to support practices like conversion therapy. Without going into great detail, trust me that these studies are bullshit and a stain on the field of psychology as a whole. There was a recent controversy around the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies “apology” about how past presidents of this organization have been involved with such work, and how those researchers attempted to contend with this terrible legacy. It didn’t go great.