One day, I was bored, and I thought to myself, “How much funding is there for research on parental mental health?” Luckily for me (and for you!) there’s a way to find this answer.

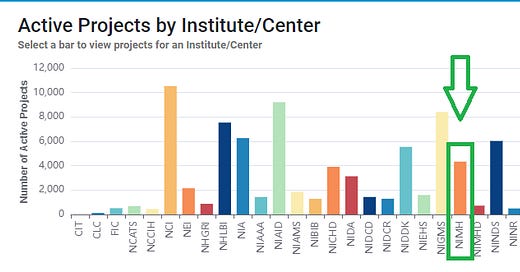

The National Institute of Health (NIH) is the nation’s lead research funding agency. Researchers apply for funding from one of the 27 NIH institutes dedicated to various diseases or topics. For example, there is the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS), etc. Most relevant to this newsletter, there is the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Currently, NIMH is funding over 4,400 grants, totaling over $2.5 billion, to scientists studying some aspect of mental health.1

As a researcher, grants are necessary for so many things: paying research participants, buying equipment/software, and paying the salaries for all the people who actually carry out your work (graduate students, research assistants, postdoctoral fellows, etc.).2 If you are what is known as a “soft money” scientist, then grants pay your salary, too. NIH grants are fiercely competitive among researchers and getting a grant is often recommended (if not absolutely necessary!) for tenure promotion at research-focused universities. NIMH (as well as other NIH institutions) have annual Requests for Applications (RFAs), where they specifically request grant submissions on various topics that they deem important and timely to study. While not a perfect barometer, an overview of the topics that are most funded from our government’s top funding agency gives us *some* sense of what we care about as a society in understanding mental health.

NIH has an online tool called the NIH RePORTER, where all active grants are publicly accessible and, importantly, searchable. With a little extra time on your hands, you can get a sense of how many grants are devoted to a specific topic in any of the NIH institutions.

First, here’s a quick snapshot of how many active NIMH grants there are that address different mental health concerns. I simply searched for each keyword within NIMH’s active grants (i.e., words in the title/abstract of the grant), and tallied the total grants that included each keyword:

Okay, so now we have a sense of the proportion of grants on some common mental health conditions.3 Next, I looked for a variety of keywords that I thought might show us grants specific to parental mental health. Here’s what I found:

On this cursory glance, only a small number of grants appear to be geared towards parental mental health. I was struck by the six that had the word “paternal” in them and, looking closer, none actually centered on the mental health of the father. Instead, they seemed interested in paternal factors related to fetal/child mental health. This would prove to be a pattern…

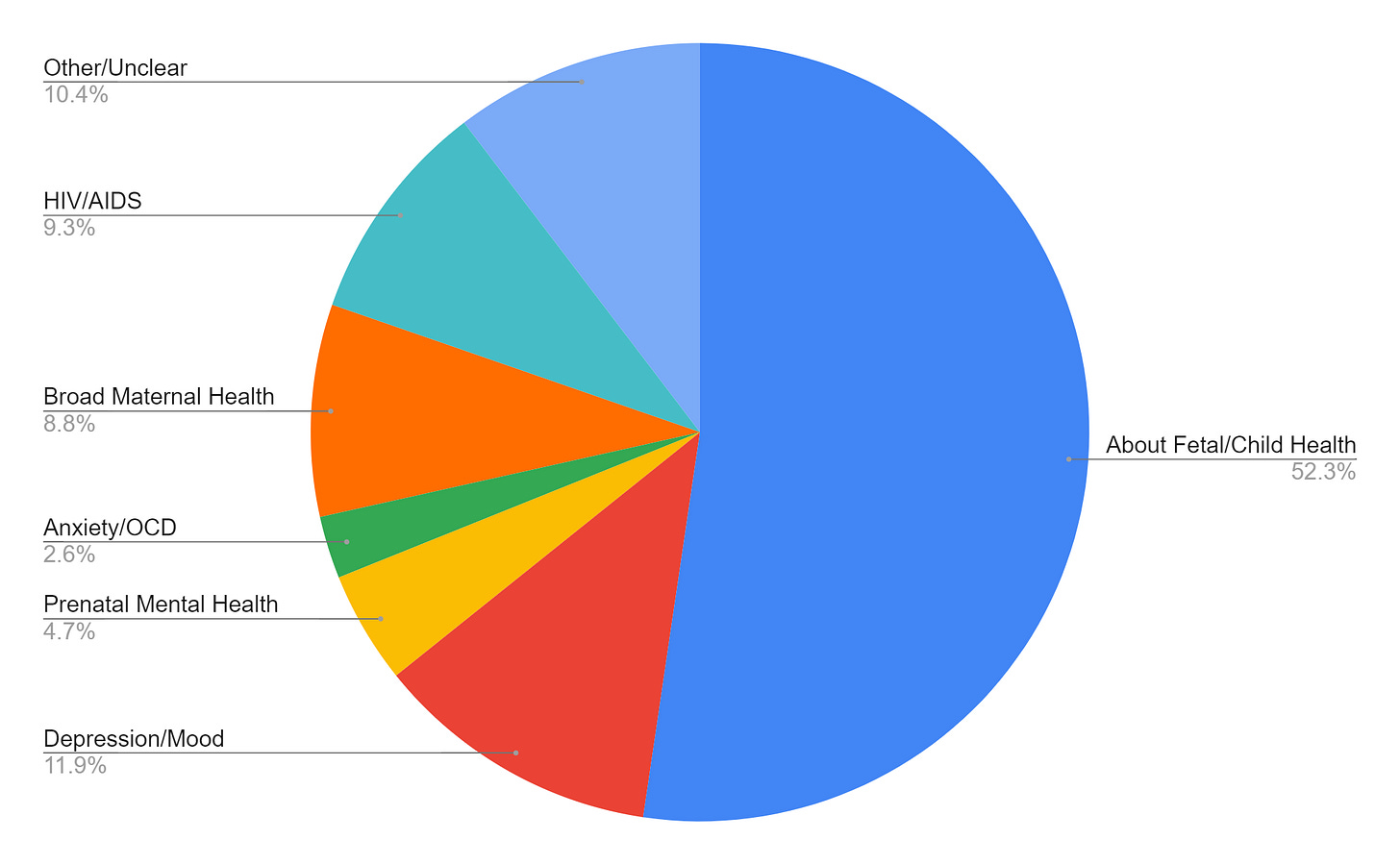

To dig deeper, I focused on all active NIMH grants that had the keyword “maternal” somewhere in the title/abstract of the grant. I then examined the titles of each grant and categorized them based on what they appeared to be studying. My categories were not mutually exclusive. This is a very imperfect system, obviously - I’m not reading all of these grants (sorry not sorry!). However, it gives us this snapshot into what NIMH is funding:

The majority of grants (52%) had titles that made it seem like they were more focused on fetal/child mental health than maternal mental health. For example, grants titled, “Prenatal and Neonatal Risk Factors for Adverse Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Childhood and Early Adulthood,” or “In-Utero Exposure to Psychotropic Medications and the Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders” seem specifically about how maternal factors affect a child’s mental health. In these studies, parental factors are more likely treated as the independent variables, the things that tell us about the outcome we're actually interested in (children's health). Parental mental health doesn't appear to be the main outcome of interest.

This makes sense, as so many mental health concerns have some type of genetic component, and maternal mental health is related to child mental health. Gestational parents are both the nature (genetics, fetal environment) and nurture part of the equation for understanding a child’s development. While there were NIMH grants that seemed to be about both parent and child mental health, and how they might influence one another, (e.g., “Role of Adolescent Stress in Postpartum Mood and Cognition”), more seemed focused on child outcomes. This isn’t a bad thing necessarily - NIMH isn’t only for research on adults. However, there *is* an entirely separate NIH institute devoted to child/adolescent health: the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). I'm not as familiar with this institute, and it's possible they don't focus too much on mental health, but it's still notable that the majority of NIMH grants with “maternal” as a key word seem to be more about the offspring than the parent.

Postpartum depression/mood concerns (12%) was the next most common topic (e.g., “A Pilot Randomized Trial of Video-Based Family Therapy for Home-Visited Mothers with Perinatal Depressive Symptoms,” or “Relationship Between Mental Health Coverage and Outcomes for Privately Insured Women with Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders,” which would also count in my “anxiety/OCD” category). This was followed by my “other” category (10%), where the grant title made it seem that it was either an animal model study (e.g., “Molecular Alterations in Primate Amygdala Following Prenatal Immune Challenge”), a study on a very specific brain/body process tangentially related to mental health (e.g., “The Nature and Function of Genomic Imprinting in Monoaminergic Neurons”), or simply a topic that just didn’t fit anywhere else (e.g., “A Couples-Based Intervention and Postpartum Contraceptive Uptake in Zambezia Province, Mozambique”). There were grants focused on HIV/AIDs (9%) (e.g., “Mechanisms and Pilot Intervention for Addressing Intimate Partner Violence and HIV in Antenatal Care”), a disease that doesn’t have its own NIH institute. Then, there were grant titles that fit into a broad mental health category (9%) rather than specifying a particular condition (e.g., “Adaptation and Assessment of a Family Intervention Designed to Improve Maternal and Child Mental Health in Resource-Limited Settings”). There were also grants specific to the prenatal period (5%) (e.g., “Maternal Stress Resilience During Pregnancy and Offspring Emotion Regulation”) and a small number of grants specific to anxiety/OCD concerns (3%) (e.g., “Predictors and Course of Postpartum Obsessions and Compulsions”).

A few other findings of note: I did not find any studies that focused on queer/LGBTQ+ parents. Only one study talked about sleep (“Daily Dynamics of Suicide Risk, Dysregulation, and Sleep Disruption Across the Transition to Parenthood”). Only one study directly addressed Black maternal mental health (“Impacts of COVID-19 and Racial Discrimination on Mental, Physical, and Psychophysiological Health in Black Pregnant and Postpartum Persons”). There were three active grants that were specific about COVID and maternal health (the aforementioned grant on Black maternal mental health, “COVID-19 Mother Baby Outcomes (COMBO): Brain-Behavior Functioning,” and “Investigating Neurobehavioral Consequences of COVID-19 Related Stressors on Maternal Mental Health and Infant Development”), though I’m sure there will be more moving forward.

All in all, it was expected, yet still disheartening, to see such few active studies focused on parent mental health funded by NIMH. There are organizations such as Postpartum Support International that provide funds for researchers specifically interested in postpartum mental health concerns, as well as private funding agencies committed to addressing health disparities (e.g., the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation). Other NIH institutions may also be dedicated to this work (e.g., National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities). I imagine (hope!) there are many researchers out there dedicated to this work without NIH funding, and that future years may show more progress in this arena.

If you want to explore on your own, the NIH RePORTER tool is free and accessible to anyone. You can search for grants in other NIH institutions, or by geographic location, or institutional setting, or other interesting metrics.

Data from this post was collected on January 31, 2022.

A gratuitous amount of money also goes directly to the university/institution where the research is taking place, but that's too complicated to get into here.

I have had multiple conversations with eating disorder researchers on the dearth of available funding for their topic. Once, when I told such a researcher that I worked with people with psychosis, she remarked, “Oh, it must be nice to get so much funding.” It was… awkward. However, such bitterness is warranted. It’s hard to argue against the idea that sexism plays a large role in why particular topics don’t get as much funding as others, especially for conditions as prevalent (and deadly!) as eating disorders. The same could be said for maternal mental health.