Formula, the Pressure to Breastfeed, and the Myth of Infant Feeding "Choice"

Two new studies suggest the way we feel about how we feed our babies affects our mental health more than the feeding choices themselves

With my first child, I had no real expectations around breastfeeding. Honestly, I didn’t think I was going to love it. My husband and I wanted to be as egalitarian in our parenting as possible, and it just felt like exclusively breastfeeding would get in the way of those goals. We were prepared to combination feed (provide breast milk and formula), but we also acknowledged that we had no idea what this journey would be like, so we were open to all possibilities.

I have previously written about how the “choice” to feed babies sometimes feels like no choice at all.1 Just like sleep training and so many other parenting decisions, the choice between formula vs. breast milk vs. everything in between is so much more emotionally fraught that it needs to be.

When I last wrote about infant feeding and mental health, I discussed how there is substantial evidence that suggests that breastfeeding may serve as a protective factor for postpartum depression, but it’s not unanimous. Breastfeeding difficulties and how strongly one has a desire to breastfeed all seem to play a role in whether or not breastfeeding is related to better (or worse) mental health.

I was hoping to write a complementary post summarizing the literature on exclusive formula feeding and mental health. Unfortunately, there is not a lot out there, and the research that does exist is confounded by the fact that many people “choose” formula because of breastfeeding difficulties, which we already know are related to poorer mental health. So I’m not the most confident that a substantial research body exists that can adequately address how formula feeding, independent from breastfeeding challenges, may be related to mental health.

However, in my search I came across these two recent studies that I think provide needed nuance in our understanding of infant feeding choices and mental health.

Formula vs. Breastfeeding vs. Combination Feeding: The Potential Harm of Feeding Ambivalence

In a paper published in Nature Scientific Reports in May, Carvalho Hilje and colleagues examined whether exclusive formula feeding, combination feeding, or exclusive breastfeeding were related to depression symptoms and mother-child-bonding outcomes. Three hundred and seven women in Germany were assessed during pregnancy and/or three months postpartum.

Postpartum depression symptoms did not differ among women who were exclusively breastfeeding, combination feeding, or exclusively formula feeding. More severe depression symptoms during pregnancy were related to a higher likelihood of exclusively formula feeding at three months postpartum.

One can imagine that if one is depressed during pregnancy, choosing to not breastfeed may have been a strategy to reduce the risk of exacerbating existing mental health concerns postpartum. Interestingly, this strategy may have been effective, based on the fact that feeding choices were unrelated to postpartum depression symptoms, though this is speculative. The researchers did not assess mother’s feeding intentions prior to birth or whether those intentions changed postpartum, factors that we know are related to maternal mental health.

Surprisingly, women who were combination feeding at three months postpartum reported more “impaired” mother-child-bonding compared to either women who were exclusively breastfeeding or using only formula. Compared to women who were exclusively formula feeding, women who were combination feeding were more likely to report concerns around infant hunger and weight as their reason for adding formula and less likely to cite reasons around convenience or simply that they did not feel like breastfeeding.

The researchers speculated that women who were combination feeding at three months postpartum possibly represented a group with more ambivalence around their feeding choices (e.g., less confidence and more guilt), which may in part have affected their subjective feelings towards their infant. They cite prior research that regardless of whether a mother decides to breastfeed or not, as long as their decisions are intentional and they are confident in those decisions, they report more satisfaction in their role as a mother.

So what affects our attitudes towards our feeding choices? Keep reading…

Breast is Not the Only Best: Mental Health Consequences From the Pressure to Breastfeed

Grattan, London, and Bueno published a paper in April in Frontiers Public Health on how perceived pressure to breastfeed affected 225 birthing parents’ mental health in New Zealand.2 Participants were between six weeks and six months postpartum and they completed various questionnaires twice, four weeks apart. Questions assessed mental health symptoms as well as experiences related to breastfeeding, including whether parents felt pressure to breastfeed and whether they were experiencing shame and stress related to infant feeding. To the researchers’ knowledge, this was one of the first investigations on how pressure to breastfeed may be related to parent mental health.

Approximately 81% of parents reported breastfeeding (either exclusively breastfeeding or combination feeding). Of the parents who were not breastfeeding, approximately 14% reported that it was because of their mental health. Parents who were not breastfeeding were more likely to report feeling pressure to breastfeed and shame regarding their feeding choice compared to parents who were breastfeeding.

Of all parents, almost 40% reported feeling a strong pressure to breastfeed and over half (52%) reported experiencing stress due to infant feeding. When parents reported a strong pressure to breastfeed, they also reported increased anxiety, depression, stress, and birth trauma symptoms. Reporting a strong pressure to breastfeed was also related to increased anxiety, stress, and birth trauma symptoms four weeks later. These relationships remained significant regardless of whether or not parents were breastfeeding, experienced difficulties breastfeeding, or had a history of mental health difficulties.

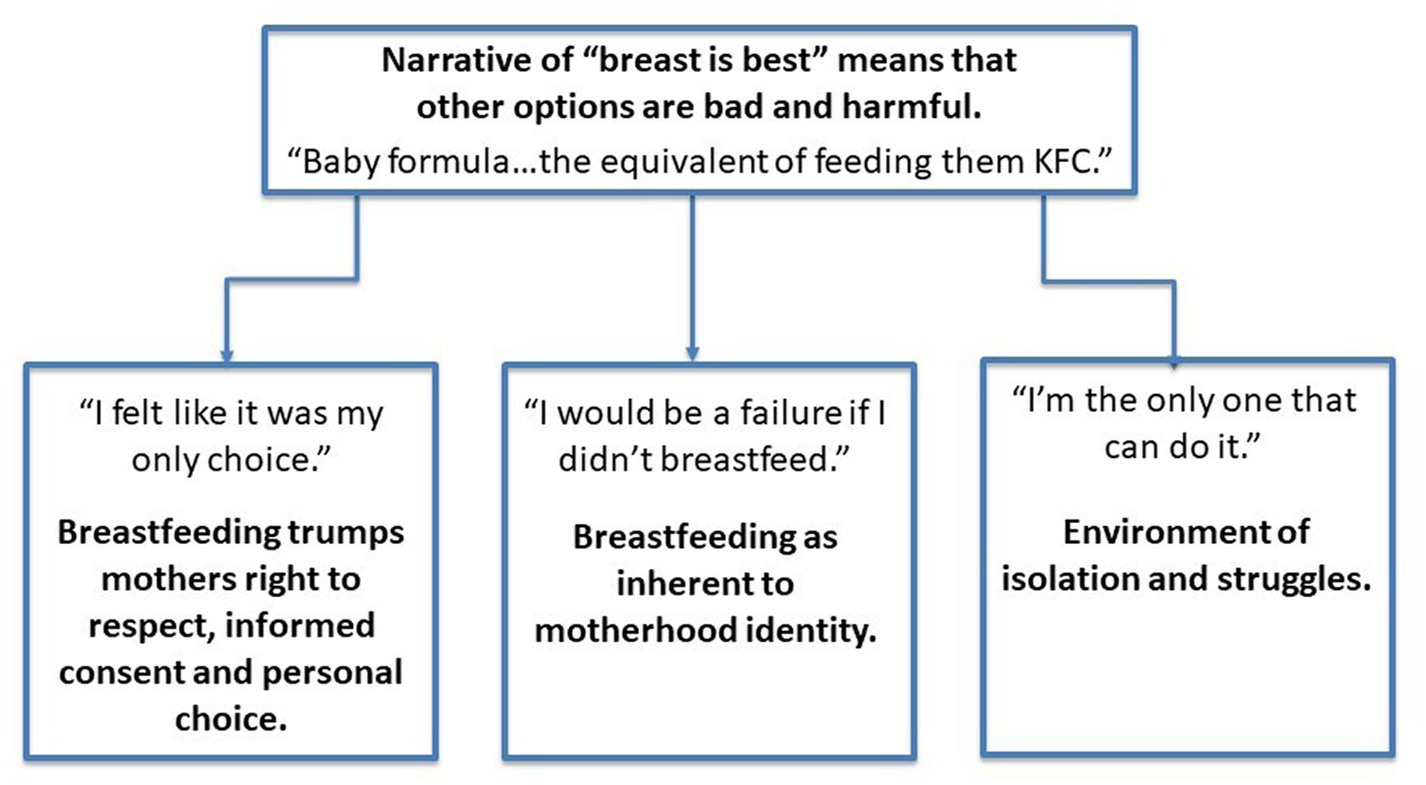

As an additional part of the study, when participants reported pressure to breastfeed or negative experiences around their feeding choices, they were also asked to describe these experiences using their own words. The researchers then used thematic analysis to better understand if there were patterns in how parents elaborated on their feelings of pressure, shame, and stress around feeding choices (see figure below).

The whole thing is worth a read, though I will try my best to summarize succinctly. Basically, the researchers found an overarching theme that when parents believed that no other option other than breastfeeding was best for their child, they overwhelmingly felt a pressure to breastfeed. Participants reported that this belief was promoted by health professionals, family, and friends.

Additionally, three sub-themes were found in participants’ responses that related to pressure, shame, and stress:

Breastfeeding trumps mothers right to respect, informed consent and personal choice: Parents reported that they did not feel they were given a choice on how to feed their infant and/or were not provided accurate information on feeding options. Participants discussed how this experience emerged through both implicit (e.g., midwives never discussing anything other than breastfeeding) and explicit means (e.g., parents denied access to formula in the hospital; parents were told that their child could not leave the NICU until breastfeeding was established).

Breastfeeding as inherent to motherhood identity: Parents reported that breastfeeding was inherent to being what they defined as a “good mother” and felt extreme guilt or like they were a “failure” if they had difficulties breastfeeding. They also reported how they had internalized myths that breastfeeding was “natural” and should be easy.

Environment of isolation and struggles: When parents felt a pressure to breastfeed, they reported feeling like they had to take on the sole responsibility around keeping their baby fed, which made them feel isolated and unsupported. Regardless of feeding choice, parents felt judged: They felt they had to be secretive about breastfeeding and about giving their baby formula.

Reading these quotes from participants broke my heart, partially because they felt so relevant to my experiences as well as many of my friends. They were also not surprising.

This is all so unfortunate: Policies meant to encourage breastfeeding may in practice put undue pressure on women to breastfeed, which affects their mental health, which in turn may lead to lower rates of breastfeeding. The researchers spend part of their discussion with ways to improve both maternal mental health and breastfeeding rates, including encouraging health professionals to provide balanced scientific information on all feeding practices and individualized breastfeeding support to all patients.

In other words, let's actually help parents feel like their feeding choices are actually choices.

These studies expand upon previous research in important ways, including the fact that both studies did not exclude parents who had a previous history of mental heath concerns. Additionally, both studies assessed a variety of feeding choices, including combination feeding, a choice that is often ignored in the literature. I also appreciated that both studies assessed parents’ experiences around their feeding choices using participants’ own words.

Taken together, these studies suggest that it may be less about how you feed your child, and more about how you feel about feeding your child, that affects maternal mental health and well-being.

Both of my children were combination fed from the start. I ended up liking breastfeeding a lot more than I expected, but we decided to switch to feeding exclusively with formula before their first birthdays. I wish I could say that I was 100% confident each time I made this decision, but that would be a lie. Particularly with my second child, who just loved breastfeeding more than my first, it felt selfish to stop just because I wanted to. However, I knew that was a lie, too. The more I could grow my confidence that this was the right choice for my family, the better I felt.

There’s so much about parenting that can feel like a no-win situation. Whatever false notions that are shoved down our throats about what is “best” for our children can make us feel like we have no autonomy, that we have to be perfect at everything to be a “good” parent, that we are alone in our struggles.

We may not have control over the messages we receive or the judgmental comments that are lobbed our way about our parenting choices, but one thing we can control is maybe the most important thing to help us all feel less anxious, less depressed, and less alone:

We can stop buying into the lies.

“We” meaning those in industrialized, Western nations where clean drinking water is (for the most part) easily accessible. Otherwise, questions around feeding choice are even more complicated.

I use the term “birthing parents” for this study because two participants did not identify as cisgender females.